The Sinking of the SS Arandora Star

By Herr Bruno Fehle

This haunting first hand account of the sinking of the Arandora Star was sent to us by

Michael Fehle from London. It was written by his grandfather, an internee during the

Second World War. Jim Leyden from Coney Island survived the disaster, others were not so

lucky.

London, November 10th, 1998

My grandfather moved to England from

Germany in the mid-30's, to run the UK office of the optical company for which he worked.

The family lived in Edgeware, in North London. The Home Office had already created a

classification for aliens living in the UK; according to how dangerous they might be if

there was a war. In October 1939, my grandfather was called before a tribunal, who

believed that he had knowledge that might be useful to the enemy, and was therefore a

security risk. He was driven home, ordered to pack a suitcase, and driven away, while his

wife and children had no idea of what was happening. He was interned with other German and

Italian civilians in a number of internment camps - former schools, holiday camps like

Butlins and the Olympia Exhibition Hall in London, before it was decided that the

internees should be deported to Canada.

My grandfather moved to England from

Germany in the mid-30's, to run the UK office of the optical company for which he worked.

The family lived in Edgeware, in North London. The Home Office had already created a

classification for aliens living in the UK; according to how dangerous they might be if

there was a war. In October 1939, my grandfather was called before a tribunal, who

believed that he had knowledge that might be useful to the enemy, and was therefore a

security risk. He was driven home, ordered to pack a suitcase, and driven away, while his

wife and children had no idea of what was happening. He was interned with other German and

Italian civilians in a number of internment camps - former schools, holiday camps like

Butlins and the Olympia Exhibition Hall in London, before it was decided that the

internees should be deported to Canada.

They were sent to Liverpool to board the Arandora Star. Between the time that my

grandfather was detained, and the time that the Star was sunk, very little communication

was allowed between him and his family, so you can imagine that my grandmother was pretty

anxious by this time. Some weeks after my grandfather's detention, a policeman turned up

at my father's school, drove him back home, and gave him 10 minutes to pack a suitcase -

his mother and younger brother had already been told that they would have to leave London

and be interned, but they didn't know where.

Eventually they too arrived in Liverpool, where there were already a large number of

women and children waiting for word on where they were to be interned. Imagine hundreds of

frightened and anxious women and children, many of whom having a weak grasp of the

language, having no idea of where their husbands and fathers were no idea of where they

were going.

Eventually word came through that they were to be transported to the Isle of Man, where

the War Office had already negotiated with the Manx government that these people would be

accommodated in hotels and guesthouses at the British government's expense. The majority

of internees on the Island were women and children, later joined by Italian prisoners of

war.

In the summer of 1940, my grandmother received word that her husband was to be shipped

to Canada - she had not seen him for eight months, and was understandably concerned that

she might never see him again.

Liverpool, June 30th , 1940

The ship had the appearance of a troop carrier being painted battleship grey and having

the rear promenade decks and the lower decks boarded up completely. All portholes were

boarded up shutting out all daylight and the ship was armed. The boarded up promenade

decks were separated from the other parts of the ship by double fences of barbed wire

reaching from floor to ceiling. The only means of communication between the aft and

forepart and to the boat-decks was through the lower cabin gangways which were closely

guarded by sentries.

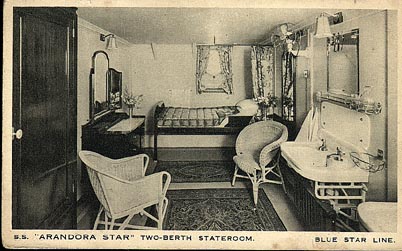

Accommodation of first arrivals, Italians, refugees from Seaton, Paignton Group, was in

two and three berth cabins with four and five men to each cabin, two sleeping on the floor

on palliasses.

The German Internees from Swanwick, who came last, were put in the ballroom aft, where

they had to live and to sleep. Approximately 120 of them had palliasses but the remainder

had to sleep on the bare floor; but no blankets were supplied to any of this group.

Lavatory accommodation for these 242 men consisted of four WCs and four washbasins. The

internees were only allowed to enter these in small successive groups closely guarded by

sentries. On the next day at 6.00 PM the greater part of the Swanwick group was

transferred to cabins on the B deck and the Italians who had been living there had to take

the ballroom as living and sleeping quarters.

The Arandora Star carried 14 lifeboats, which on average hold 50 to 60 persons

each. In addition there were the usual number of life rafts. There was no official issue

of lifebelts, but belts of various designs were lying about and it was left to everybody

to provide himself with such a belt if thought necessary. No instructions whatever were

given for the possible event of being shipwrecked; i.e. no boat drill was held, no one was

instructed in the proper use of a lifebelt, no instructions were given as to how to

proceed in the event of an emergency.

The ship sailed without escort or convoy and on Monday July 1st she was

pursuing a short but continuous zigzag course. All outer lights were extinguished and the

ship was absolutely dark. With the numerous sentries on deck and the guns silhouetted

against the sky the ship had the definite appearance of an armed merchantman troop carrier

and she looked sinister, like a veritable coffin.

On July 2nd at 7.05 AM a torpedo hit the Arandora Star below the

waterline shaking her by a violent explosion. The light in the cabins and inner gangways

went out a few seconds afterwards. Apparently the electrical installation was put out of

order immediately; no alarm was sounded and whoever was able to do so went from cabins and

living quarters to the decks to reach one of the lifeboats.

Everyone tried to save his life as best as possible. There was no visible attempt made,

however, to organise the evacuation of the ship, but officers and men of the SS Adolf

Woermann who were between the internees from Swanwick lowered the last six boats in

good order. From the 14 lifeboats that were carried by the Arandora Star, one was

destroyed by the explosion when the ship was hit, one could not be lowered and went down

with the ship, two were smashed during the process of lowering, either the gear being in

bad condition, or due to misproper handling. Four boats got down safely but with very few

survivors in them, as it seemed to be the desire of the people lowering the boats to get

these away from the ship as quickly as possible.

The last six boats that the Woermann crew handled were filled almost to

capacity, two or three of them almost exclusively with British soldiers. Captain Burfeind

of the Woermann who supervised and organised the lowering of these boats stayed

with others of his crew at his post and lost his life. He had the situation well in hand

and it is due to his endeavors that many were saved.

Many rafts, boards, benches, etc., were thrown into the water, but certainly not all

that were available for this purpose, and those people that could not get to the boats

mostly jumped overboard, to hang on to them as best they could. In the disorder that

occurred, it happened that some people who were already in the water and making for the

rafts were hit by rafts that were thrown down and became injured some of them fatally.

Many people, especially sick and older ones, and those from the lower part of the ship

could not reach the open decks or could not make up their mind to jump overboard. The

majority of these stayed onboard and finally went down with the ship, clinging to the

railings, and in this way many lives were lost. There were many Italians between them, as

they were mostly of middle age or older.

It must be said that the lifeboats and tackle were in a neglected condition, which

caused two boats to become useless, another filled with water because the stoppers were

missing, and two of the motor boats did not operate through lack of petrol. There were

petrol canisters in these boats, but they were found to be empties.

As mentioned before, several boats were lowered with less than 10 occupants but all the

boats did their best to pick up survivors from the water and from wreckage pieces to which

they were clinging. The boats were handled by crew and survivors, but none of the boats

had its proper crew. The boats kept together to the best possible extent within short

distance from the Arandora Star.

The ship was settling with an increasing lift and it appeared that she broke in two by

a second, apparently a boiler, explosion, before she finally sank. It was a dreadful sight

as many people were still on the upper decks holding on to the railings. The Arandora

Star sank at about 7.40AM.

The sea was fairly calm with slight swell and occasional drizzle. At 11.00AM a seaplane

appeared and the lifeboats lit red flares. After circling several times the plane made off

and returned shortly afterwards when it dropped a message that help would be coming soon.

At about 2.30PM a destroyer HMCS 83m St. Laurent, approached and at once started

to take on board survivors off the rafts, while the boats were making for the destroyer,

which had also lowered its own motor-launch. This picked up survivors who were swimming in

the water or clinging to the rafts. The swell had increased, but in spite of this the

difficult operation of taking the survivors on board was capably carried out by the crew

of the destroyer without any mishaps.

On board the destroyer everything was done to make survivors as comfortable as

possible. Many of them were very exhausted, as they had been in the water for up to seven

hours, but also those from the lifeboats suffered from cold and exposure, as they were

very scantily clad, mostly in pajamas. Quite a number of survivors were black over their

whole body from bilge or fuel oil, and these were cleaned immediately. Hot rum and cocoa

and biscuits were shared out and clothes and blankets were provided, so everyone could get

warmed up and revived. All those needing medical attention were taken care of by the

ship's doctor who did his utmost to help. It must be said that the treatment of all

survivors regardless what they were, or where they came from, by officers and crew, was

excellent in every way, and every one of the survivors will thank them in his heart for

their kindness.

On Wednesday, July 3rd , at 8.45AM, Greenock, on the Clyde, was reached.

After disembarkation of crew and soldiers from the Arandora Star, the internees

were put ashore in three groups. Germans, Italians, and sick people. The Italians and

Germans were marched off. The sick remained on the quay for full two hours without

shelter, and had to march then to a first-aid station, where they had to wait another 2½

hours. During the last hours, cups of tea and biscuits were served. Finally ambulances

arrived which brought them to Mearnskirk Hospital, Newton Mearns. They arrived there at 2

pm, and were treated as hospital patients in an excellent way.

No preparations had been made for the accommodation of the other group of survivors

that was marched off from the quay, most of them barefoot, to a factory building ½ a mile

distant. No blankets were available, and no food whatsoever was given before 1 o'clock,

when they received a slice of bread with corned beef and a cup of tea, which was all the

food issued that day. No water was given for washing until late in the evening or the next

day, lavatory accommodation was two WC's, for 250 men, there were no beds or palliasses

and hardly any blankets. All those survivors were in bad need of a hot shower, and of some

accommodation to get a good night's rest, and of some proper hot food as well as warm

clothes. Instead of this they had to endure another night and day of exposure in their

torn and oily clothes, or better said rags. As a result of this a further number of

internees became so exhausted that they too had to be taken to hospital.

As far as we can make out the numbers of survivors were as follows:

Italians: 266 out of 740

Germans from Swanwick: 206 out of 242

Germans from Seaton 82 out of 184

Germans from Paignton: 32 out of 50

Total: 586 out of 1,216

We wish to put on record that all reports about unpleasant incidents of fighting

between the shipwrecked during the period of rescue are untrue and lack basis or

foundation. The ship's crew and the internees assisted each other in a most friendly and

helpful spirit, and when taking people into the boats from rafts, wreckage, or those who

were swimming, no differentiation whatsoever was made.

Signed:

B Fehle for Swanwick Group

C Kroning for Seaton Group

Kreauzer for Paignton Group

R. Vicki-Borghese for Italian Group

Mearnskirk Hospital, Newton Mearns, July 10th 1940.

London, November 10th, 1998

When the Star was sunk, the news reached the Isle of Man a long time before anyone was

notified whether their loved ones had survived, or where the survivors were being held. It

was not until September 1940 that my grandmother heard that her husband was still alive,

and it was not until late in 1940 that he was shipped to the Island with a number of other

internees to be held for the duration.

After the war, the family moved back to Germany, where my grandfather started working

again for his old optical company on the outskirts of Berlin, then under Russian control.

When the Russians strengthened their hold on East Berlin, he moved the family to a small

town near Frankfurt am Main in West Germany, where he lived until the early 1970's.

My father emigrated to the USA in the 1950's, where he worked for a precision

engineering company, until he met my mother, an English woman from Dover who had moved to

New York in order to set up an office of the employment agency for which she worked. They

moved back to England in 1966, where they were married, and then moved again to the town

where my grandfather lived, and raised a family.

In 1976, he decided to move the family back to the Isle of Man, where he had spent his

childhood, and where I lived until 1995 when I moved to London to work.

My grandfather moved to England from

Germany in the mid-30's, to run the UK office of the optical company for which he worked.

The family lived in Edgeware, in North London. The Home Office had already created a

classification for aliens living in the UK; according to how dangerous they might be if

there was a war. In October 1939, my grandfather was called before a tribunal, who

believed that he had knowledge that might be useful to the enemy, and was therefore a

security risk. He was driven home, ordered to pack a suitcase, and driven away, while his

wife and children had no idea of what was happening. He was interned with other German and

Italian civilians in a number of internment camps - former schools, holiday camps like

Butlins and the Olympia Exhibition Hall in London, before it was decided that the

internees should be deported to Canada.

My grandfather moved to England from

Germany in the mid-30's, to run the UK office of the optical company for which he worked.

The family lived in Edgeware, in North London. The Home Office had already created a

classification for aliens living in the UK; according to how dangerous they might be if

there was a war. In October 1939, my grandfather was called before a tribunal, who

believed that he had knowledge that might be useful to the enemy, and was therefore a

security risk. He was driven home, ordered to pack a suitcase, and driven away, while his

wife and children had no idea of what was happening. He was interned with other German and

Italian civilians in a number of internment camps - former schools, holiday camps like

Butlins and the Olympia Exhibition Hall in London, before it was decided that the

internees should be deported to Canada.